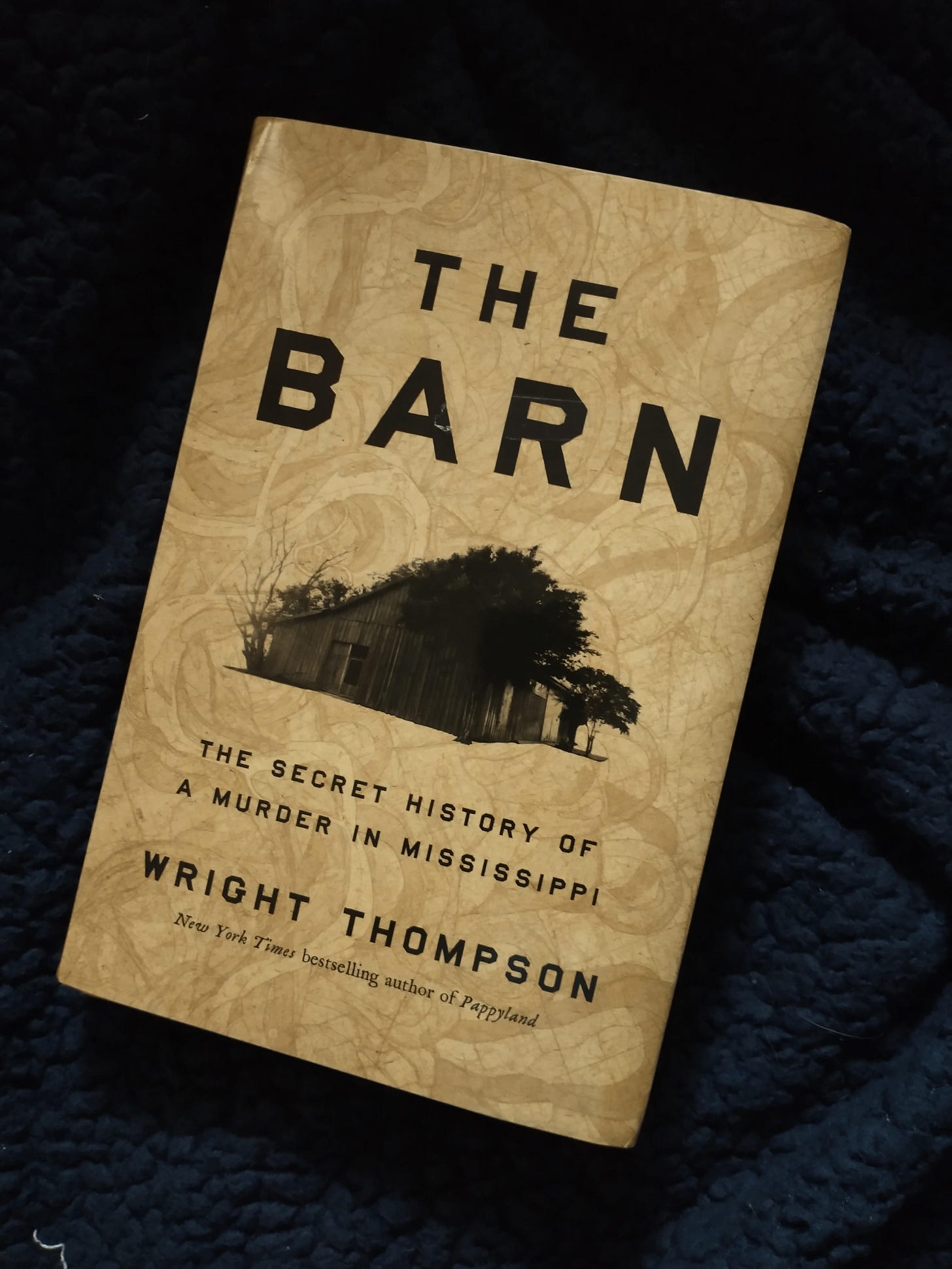

The Barn: A Book Review

The unraveling and road map to show how the murder of a 14-year-old boy came about and how it sparked the Civil Rights movement in the United States

Wright Thompson, author of The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi, and I were both born in 1976. That was the year Rocky was released and went on to win the Oscar for Best Picture the following March. In 1976, Elvis was still alive, but would be dead the following August.

1976 was also the year the United States of America celebrated the Bicentennial anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

It was a different time.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” - Declaration of Independence

I post that small portion of Thomas Jefferson’s writing to remind you what and how some people thought about others back in 1776. Unfortunately, it was not the way everyone, including the Founding Fathers, thought about “all men.”

Emmett Till

I remember learning, in my 11th grade AP History class in New Port Richey, Florida, about Emmett Till, the 14-year-old black boy who was killed by a group of white men.

I didn’t recall the reason he was murdered was because he’d allegedly whistled at a white woman. I could only recall or knew very little, if any, facts about the case, before reading The Barn.

Wright Thompson, who grew up in the heart of the Mississippi Delta, just a few miles from the barn Till was killed in, did not learn about Emmett Till until he left home for college — in Missouri.

That’s hard for me, and Thompson, admittedly, to comprehend.

That would be somewhat like my 9-year-old son not learning that President Joe Biden was born in Scranton, the next town over, until he went off to college — in Virginia.

Granted, celebrating the birth home of a future president is a little different than bringing the nation’s attention to the foreboding barn where a 14-year-old black boy was murdered out of hate.

While Biden now has an expressway and a street in downtown Scranton named after him, Thompson has made it his mission and work the last three years to bring the same attention that Emmett Till — his life and death — deserves, not only within the borders of the state of Mississippi, but throughout the United States and beyond.

The last several years have seen unprecedented times and tragedies in relation to race in this country.

In 2015, Eric Garner, a black man, died after being in the illegal choke hold of an arresting police officer in New York. In 2020, George Floyd, a black man, died after a Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin, held his knee on the back of Floyd’s neck for almost nine minutes.

The video, in which Floyd repeatedly cries out, “I can’t breath,” is troubling to watch. Now imagine being the witness to the Till murder, who can still hear him calling out, “Mama, save me!”

Generation Gap

I feel that for many of us who grew up as members of Gen X, racism is hard to grasp, having grown up in a culture that celebrated black people. We are a generation that grew up idolizing Michael Jordan and purchasing the products: Nike, Gatorade, Wheaties, he promoted. “Be like Mike,” was more than a tag line, and a Michael Jordan poster hung on my bedroom wall as a boy.

We all watched a late night talk show, hosted by Arsenio Hall. We purchased CDs, danced to and watched videos by musicians such as Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, Janet Jackson, Bell Biv DeVoe, Boys II Men, MC Hammer, N.W.A., LL Cool J and others.

We all watched in horror on television as a group of men, again police officers, beat the hell out of a black man named Rodney King on the side of a Los Angeles freeway.

We then watched “live” on television as South Central Los Angeles went up in flames. The late ‘60s riots had returned, in living color, to our ‘90s oasis.

That being said, America can still feel largely divided by race. A simple drive through any city can show you that, whether it’s Scranton, Philadelphia or Flint, Michigan.

I’ve spent time living in Florida and Northern Virginia, but I’ve never lived in the Deep South, like Thompson. After reading his book, I’m glad I didn’t, if for no other reason than the weight and baggage of dealing with what Thompson unravels in this book, one of my top books of 2024.

In The Barn, Thompson delves deep not only into what happened that August night in 1955, a night that would catapult the Civil Rights movement here in America, but digs into a centuries-long investigation, from New World explorers, to the Civil War, to Reconstruction, to Jim Crow, World War I and World War II, to help explain just how that group of grown men ended up torturing and lynching Emmett Till.

It is a fascinating study in American history, politics and economics.

Till, visiting relatives from Chicago, was naive to the unwritten laws of Mississippi.

Step off the sidewalk if a white person is coming. Always address white people with “Sir” or “Ma’am.” Black men should never make eye contact with a white woman.

Some of these rules I was unaware of until I read this book. And learning about the daily customs of living under this double standard is troubling, especially to those of us living on the doorstep to 2025.

One aspect of the book I liked best is that The Barn is not a patronizing or condescending piece of woke ideology.

As Thompson readily admits throughout the book, some of his own relatives have played roles in upholding the hidden history of Mississippi, and this includes his own misguided past behaviors when it came to the South and the Lost Cause, such as displaying a Confederate flag in his college dorm room.

But Thompson also had relatives who tried to do their part in changing this culture, a legacy Thompson now continues.

When reading history, it is sometimes easy to think that whatever you’re reading about happened so long ago.

Emmett Till, if he were still alive, would be the same age as Martha Stewart and Bob Dylan. In many ways, Till is still a contemporary figure, even today.

In addition to race relations, Thompson also explores and shows how the judicial system that made the trial of the two men charged with Till’s murder, J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant Jr., was a complete farce, thanks to a rigged jury and judge.

He also shows the impact the murder had on Till’s family members, including the group of young cousins he was down visiting in Mississippi, and the memory of that particular night and how it impacted all of them for the rest of their lives.

Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, who insisted on Till’s body not only being brought home to Chicago, but then displayed in an open casket, became the spark that lit the fuse in the fight for Civil Rights in America.

In Montgomery, Alabama, after hearing a speaker describe Emmett’s murder at a political event at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Rosa Parks, four days later, refused to move to the back of the bus.

And while the barn still stands where it did nearly 80 years ago, Thompson sheds light on how the evil actions of that particular night have also impressed upon and encouraged generations of not only black, but white people too, in a quest to overcome centuries of mistreatment of black people in America.

This is one of the most moving books I’ve ever read, including one scene in the beginning of the book I read in my car before going into work that was a complete gut-punch.

There are many other scenes, some infuriating, some loving, and an entire community of sympathetic and inspiring people and stories in this book that will stay with me for a long time.

If it was Thompson’s goal to raise awareness about Emmett Till’s murder, he’s done that. If it is to change the way people think and feel about others, and to impact the future, he’s done that too.

To learn more about Emmett Till, but sure to check out the Emmett Till Interpretive Center.

Thompson is an incredible writer. I'm lining this up to read early in the new year.